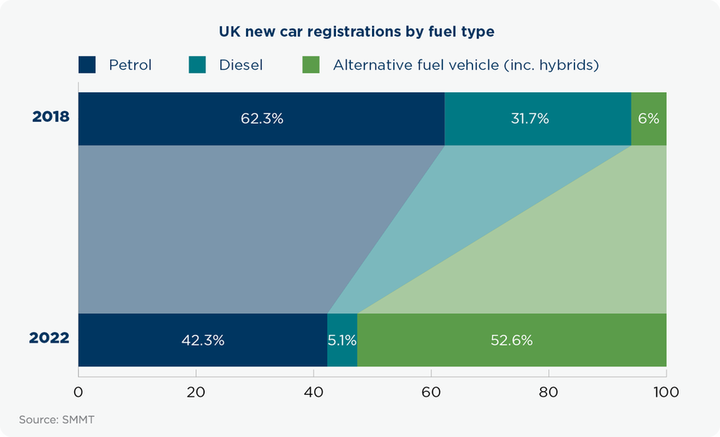

You can’t argue with the numbers. With sales of electric vehicles (EVs), including plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) set to account for almost a fifth of all new cars worldwide by the end of 2023, that’s no less than a 35% increase on 20221.

The role EVs are playing in the climate change fight is crucial despite slowing sales, disruptive shifts in government policy and negative public opinion regarding price and charging infrastructure.

According to the International Energy Agency, there were 26 million EVs on the world’s roads in 20222. That number is expected to increase to 40 million by the end of this year. China remains the world’s largest EV market with 40% of total volume, with Europe second, followed by the US and South Korea.

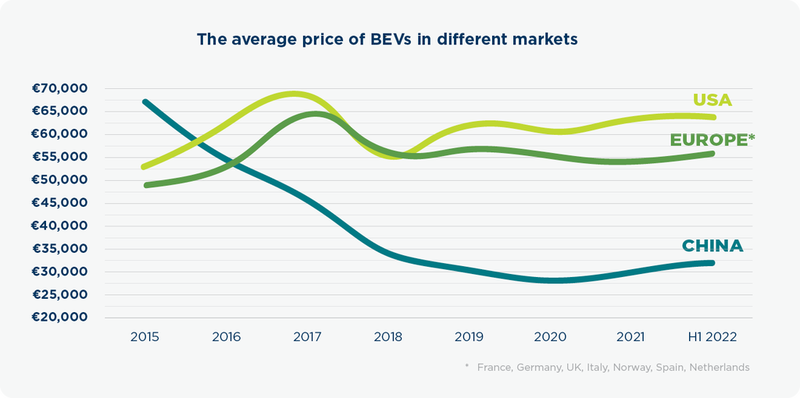

The market share for new EVs continues to be powered by government policy, anti-ICE legislation, environmental concerns and a wider range of vehicles to choose from at increasingly affordable price points. But are financial inducements, law changes and ramping up the attractiveness of EV adoption enough to support the transition to electric?

Are petrol and diesel vehicles’ days truly numbered, or might e-fuels offer a reprieve? And how do used EVs and commercial vehicles factor into the ubiquitous drive to decarbonise automotive?

THE US

PERSPECTIVE

Jonathan Smoke

THE EU

PERSPECTIVE

Jürgen Stackmann

THE AU

PERSPECTIVE

Matthew McAuley

THE LCV PERSPECTIVE

Matthew Davock

The carrot and the stick

The UK government’s recent U-turn on its ambitious pledge to ban the sale of combustion engine vehicles by 2030 came as an unsettling jolt for many manufacturers, with Ford accusing the government of sending mixed messages. On the other hand, Toyota has welcomed the change, describing it as ‘pragmatic’. The shift came amid ongoing tussles between manufacturers and the EU regarding ICE phaseout deadlines and tariff charges that will be applied following cut-off dates, as vehicle makers seek to manage production volumes and their profitability.

If we leave aside the practical rights and wrongs of extending the deadline to 2035, in line with most of the EU and many parts of the rest of the world, it’s important to note the sheer wave of disquiet that this major change of heart has caused in automotive, reflecting just how important government words and actions are in relation to the EV transition.

It remains to be seen what effect the current UK 2035 cut-off date will have on demand for new EVs. Manufacturers will, of course, be keeping a close eye on how the decision impacts buying behaviour and sales. The fear is consumers will further delay their buying decisions just as manufacturers need them to be motivated to make the change from ICE to EV.

In the UK, EV consumer adoption was being incentivised by numerous pieces of legislation, including the plug-in grant (now ended), road tax exemption, financial help to aid the installation of home charging, and other bonuses such as exemptions from various congestion charges and free parking in certain areas. Additionally, a lower rate of tax for company car EVs meant that fleet EV growth was also being driven by the proliferation of salary sacrifice schemes. These have proven to be a big draw to energy companies. Octopus Energy, the UK’s third-largest supplier, has recently gone to great lengths to promote such schemes. However, the UK is now the only major European market without significant consumer incentives for EV uptake.

In the US, a tax credit of up to $7,5003 is promised with the purchase of a new EV. Many states are also offering tax credits, rebates, and even access to traffic lanes usually reserved for buses or vehicles with several occupants. That tax credit was recently extended to 2032 by the largest federal legislation ever to address climate change, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The IRA removes the per-manufacture cap on the EV tax credit, meaning there’s no limit on the number of EVs that a manufacturer must sell to qualify for it. The act also provides tax credits for the purchase of commercial EVs, including buses and delivery trucks. Not only that, but it has also set aside $7.5 billion for extending the US charging infrastructure.

In continental Europe, many governments offer EV adoption incentives. For example, Norway (where, currently, 80% of new cars bought are electric) has an approximate £9,000 incentive for new EV purchases. Germany promises a “climate bonus” to consumers who switch. Earlier this year, the incentive was reduced to €3,000 and the Mercedes GLA PHEV is no longer eligible. Additionally, manufacturers are only obliged to grant 50% of the government part for BEVs but nothing for PHEVs.

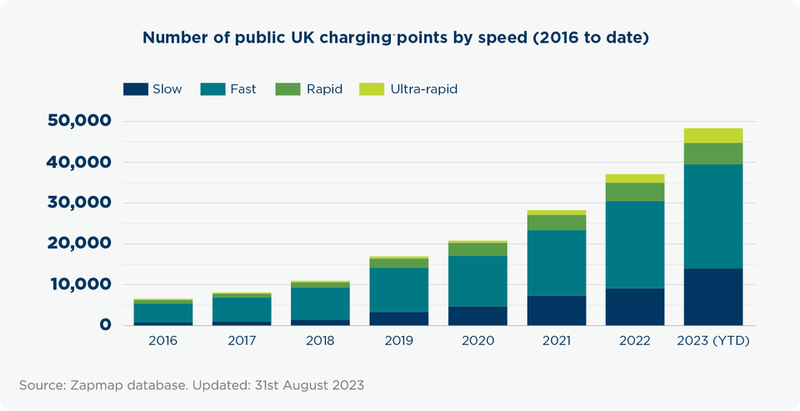

Meanwhile, the EU has vowed to have one million public EV charging points installed in member states by 2025.

Broadly speaking, most administrations in the developed world have set ambitious targets to accelerate electrification and decarbonise, with EV adoption the jewel in the strategic crown. But can they do more?

Must try harder?

It was recently revealed that a new EV is registered every 60 seconds in the UK. However, Cox Automotive believes that governments, in Britain and further afield, must take more action to boost consumer adoption – but for used EVs too. We have previously said that a healthy market for used will help the new EV market reach its full potential and that the government should seriously consider intervening to boost the viability and public perception of used EVs. Without strong consumer used appetite residual values will be poor with the knock-on impact to new EV lease costs impacting new sales and therefore supply. Investment is needed in charging infrastructure, clearly, but the government can also help through subsidies or loans for used EVs and by easing public fears about battery capacity in these models.

One innovation that should help, though still in the early stages of development, is bi-directional charging. It means stationary EVs can send unused energy either back to the grid or, indeed, to a driver’s home, during certain hours of the day.

Octopus Energy says the still-developing technology will eventually help reduce home energy bills which means that an EV effectively becomes a mobile power pack that gives something back. This will mean a financial benefit to EV owners and should equate to a lower total cost of ownership.

The fact is though, such technological developments need a bigger PR push if consumers are going to think more seriously about buying an EV, especially given the UK government’s amended combustion ban deadline. It may have the negative knock-on effect of making prospective buyers think twice now that there’s more time to decide.

UK political leaders must also seize the opportunity provided by their ICE ban date change, perhaps by offering new financial incentives for adoption. That could include reducing VAT on EV sales and/or slashing the cost of public charging, or at least making it equal to the cost of charging at home (it currently costs twice as much to charge publicly).

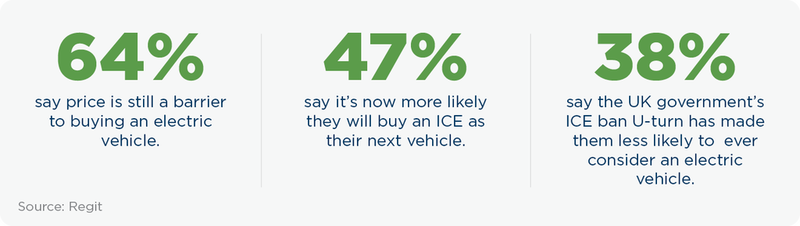

A recent Regit survey found that nearly half (47%) of motorists said they are now more likely to buy an ICE car as their next automotive purchase. Of those asked, 38% said the government’s deadline U-turn has reduced the likelihood of them ever owning an electric car.

An EV proving ground

Cox Automotive has consistently said that the used market for EVs is the proving ground that supports new EV sales. Growing used EV volumes (and appetite for them) have pushed them higher up the consumer choice list. Their residual values will remain volatile as technology and drivetrain improvements continue to evolve. EVs are offering strong margins for dealers and mean a more affordable and straightforward option for consumers.

In the US, used EVs are eligible for tax credits of up to $4,000, or 30% of the sale price, whichever is the lower. And in Europe, many countries have a similar incentive. In the Netherlands, for instance, a used EV purchase can include a subsidy of up to €2,000 under certain conditions.

Another recent survey, run in partnership with Regit, said that currently only 25% of UK motorists admit they will one day buy electric. However, stumbling blocks remain, most notably price (72%), range (66%) and charge times (61%).

In conclusion, more and more people want a new EV but many are rightly concerned about the price tag and imbalance in terms of charging cost. The hesitant buyer in the UK won’t have been helped by the new 2035 milestone, while manufacturers’ reaction to it suggests widespread frustration. Perhaps it will have the marked effect of causing a slowdown in new car supply? If that’s the case, then prices of EVs won’t come down and the brakes will, temporarily at least, be put on adoption. For most consumers, the car is an essential item so more consideration has to be given to the cost of transition impacting on the majority of people which is in the used market.

We must keep in mind that the UK, while the second-biggest new car market in Europe, accounts for just 2.5% of sales worldwide. Automotive today is a global business; the amended deadline won’t seriously affect the manufacturing strategies of large, internationally focused manufacturers.

Ultimately, the pace of transitional change to EVs will depend on factors including clear and consistent government policy, private sector investment and consumer demand. Additionally, as manufacturers are evidently no longer investing in ICE technology, EV supply will be a governing factor in their uptake. As we roll towards 2035, buyers desiring the latest technology in their next vehicle will have little choice other than to purchase an EV.

Making EV manufacturing more sustainable

While EV adoption is the focus of decarbonisation throughout the developed world, significant questions must be asked about how their manufacture can be made more sustainable.

The environmental implications of how they are made are complex and concerns include how the raw materials used in EV batteries, including lithium, cobalt and nickel, are mined and processed. They come from countries including Chile, Australia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

There are also energy-intensive processes involved in manufacturing the batteries, which, according to reports, produce a significant amount of CO2.

Sustainable manufacturing is invariably focused on reducing environmental harm and conserving natural resources. New methods to harvest lithium, such as “direct lithium extraction” are evolving to help make mining less water intensive. Sustainable battery production is showing encouraging signs of evolution also. Practices such as deploying more renewable energy resources in battery production, reducing waste and sourcing materials with a greater emphasis on circularity, are helping.

Fuel's gold: EV alternatives

The worldwide drive to net zero may spell the end of the combustion engine as we know it, at least in the new vehicle market, but in this past year the attention given to so-called e-fuels has offered a glimmer of hope that ICE vehicles’ days may not be altogether numbered.

E-fuels including e-kerosene, ICE hydrogen, e-methane and e-methanol are synthetic sources of energy produced using renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power. They can be used in conventional petrol and diesel engines. The fuels release CO2 into the atmosphere when used but those are equal to the amount taken out of the atmosphere to produce the fuel – making them CO2-neutral.

Such fuels hit the headlines in Europe earlier this year when Germany declared opposition to an EU law ending sales of CO2-emitting cars by 2035. The objection demanded that sales be allowed of new cars with combustion engines after that date if run on e-fuels.

However, e-fuels are not yet produced at scale and they are extremely expensive to make.

Porsche is developing an e-fuel plant in Chile that is expected to produce just 130,000 litres of the fuel per year starting in 2024. In Italy, Audi is developing an e-fuel plant and the US Department of Energy is thought to be funding several projects related to e-fuel production. Several other European countries are doing the same. However, it’s thought that the sheer expense of making e-fuels may mean that it never becomes a mainstream way to power vehicles. So, while it’s caused some excitement, it will most likely become the preserve of a minority of driving enthusiasts with money to burn.

More widely used and produced, especially in Latin America, are liquid biofuels. Said to be “carbon neutral”, they are derived from biomass, i.e., plant, algae or animal waste. It’s commonly advocated as a cost-effective and less harmful alternative to petrol and diesel. The type in greatest production is ethanol (ethyl alcohol) which is made by fermenting starch or sugar. The second most common is biodiesel, made primarily from oily plants. The latter has been used in European diesel engines but has been difficult to develop economically. In practice, the industrial production of agricultural biofuels can reportedly result in additional GHG emissions. Its production can also affect the economics of food pricing and availability.

Hydrogen is another alternative fuel with the potential to cut transportation emissions. The most abundant gas in the universe, hydrogen is used to power fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) which emit only water vapour. FCEVs are currently more expensive than battery electric vehicles and the refuelling infrastructure throughout Europe is very limited. Additionally, the production of hydrogen is energy intensive and it can be difficult to store and transport. Although hydrogen is often spoken of in the same terms as BEVs, technology has a long way to go before it can be seen as an affordable and realistic option.

Fleets and commercial EVs

In terms of EV adoption, fleets are leading the way in most of the countries already mentioned. In the US, commercial fleets are expected to account for 40% of all EV sales by 2026.

Some of the world’s biggest consumer brands have set out firm strategies for going electric. Amazon has ordered 100,000 delivery vans from Rivian. Walmart, UPS and FedEx have also outlined plans to have more EVs in their fleets.

In the UK, electric light commercial vehicles (LCVs) will make up more than 7% of all new registrations by the end of 2023, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders (SMMT)4. Additionally, more than a fifth of fleets said they are planning to order electric vans in the next 12 months, according to a survey by the 360 Media Group5. Additionally, last year saw the biggest annual increase in the number of electric van registrations, a growth of 30% on 2021.

Industry experts say fleets are much more agile, and more understanding of the shift to net zero, than they used to be. Moreover, new entrants in the EV new vehicle market, including Chinese giant BYD, have reportedly targeted UK fleets to get a clearer idea of their needs. Fleet managers tell us that new vehicle supply has improved dramatically and that’s partly thanks to new entrants’ activity.

In conclusion, when governments make bold pronouncements about how we’re all on the same road to net zero, the removal of financial incentives can only damage the willingness to go electric.

Perception is everything. Clear messaging on charging infrastructure plans and a more rigorous approach to EV education and its developing technologies are needed if this zero-emission journey is to be made easier for everyone.

PERSPECTIVES

References

- Developing a New Retailer Model…. Stellantis.com

www.media.stellantis.com/em-en/corporate-communications/press/developing-a-new-retailer-model-in-europe-with-our-dealer-network-to-enhance-customer-experience - Agency model: it’s coming to UK car dealers… Auto Express

www.autoexpress.co.uk/buying-car/357915/agency-model-its-coming-uk-car-dealers-what-does-it-mean-buyers - Changing the Topic of the Direct-to-Consumer Conversation

www.bcg.com/publications/2023/engagement-centered-direct-to-consumer-sales-strategy - Mercedes ‘delighted’ with agency model feedback… cardealermagazine.co.uk

cardealermagazine.co.uk/publish/mercedes-delighted-with-agency-model-feedback-despite-mixed-reaction-and-market-share-dip/279576 - Mercedes-Benz wins landmark court case… drive.com

www.drive.com.au/news/mercedes-benz-federal-court-case-fixed-prices-australia/ - Dealer survey reveals agency misery. Goauto.com

premium.goauto.com.au/dealer-survey-reveals-agency-misery/ - BYD Auto. Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BYD_Auto

Jonathan Smoke

Chief Economist, Cox Automotive INC.

EV manufacturing and the environment…

Mining of minerals used in the production of EV batteries is environmentally damaging. But while EVs have greater environmental impact in production than ICE, EVs are far cleaner over the full lifecycle of a vehicle. Fortunately, there are many steps to be taken that can improve the environmental impact of production as well. One key area is battery recycling. The long-term environmental impact can be reduced by reusing minerals rather than mining new materials. Additionally, advancements in battery chemistry (like LFP) can reduce mineral requirements. Lastly, OEMs are getting more involved in upstream battery sourcing to ensure ethical and responsible practices.

Another challenging area is ethical labour conditions. Obtaining virgin lithium from mines in specific geopolitically fraught locales also presents ethical problems since most labourers work in less-than-optimal conditions. Similar to the environmental impact, this can also be addressed by bringing the supply chain into the US and its allies. The US is behind Europe and China, but several landmark legislative accomplishments in recent years are leading to a ramping up of mining and battery manufacturing in the US and with key allies and trading partners.

Jürgen Stackmann

Director Future Mobility Lab @Uni St.Gallen, Lecturer @HfWU Geislingen

EV manufacturing and the environment…

Regarding BEV manufacturing, the battery pack, including cells, creates around 30-40% of the vehicle's material value (depending on the market segment). Battery system manufacturing creates two distinct sets of environmental challenges:

- Raw materials (rare earth metals such as cobalt, lithium, etc.…) are required for cell production. These are mostly found in the southern hemisphere, requiring high levels of fresh water and energy for transportation.

- High amount of energy required in its manufacturing process.

Both challenges need to be and will be improved through R&D progress with time (i.e., cells without the need for cobalt).

The true answer to set 1 (raw materials) lies in a thorough application of circular economy thinking. Re-use of materials for future BEVs is a must. It's hard to believe that the present running car parc (around 350 m cars in Europe alone) can be replaced by BEVs all using fresh raw materials from around the world. I understand that significant OEMs are heavily investigating opportunities to set up circular material streams, especially for battery manufacture, not only for sustainability purposes but also to warrant regional supply chains for materials that have their origins on other continents.

High energy consumption is the second significant environmental (and cost) concern, especially in battery production. The avoidance of ‘brown’ energy (coal, oil, gas) has the highest priority for all battery manufacturers trying to shift to green energy usage for existing plants or even shift plant locations in countries with low CO2 energy footprints as Scandinavians have demonstrated.

Other vehicle parts will, with time, shift into green steel (hydrogen-based), with high degrees of re-use of recycled materials.

Mathew McAuley

Director of Strategy & Marketing, Cox Automotive Australia

EV manufacturing and the environment…

Australia is a major exporter of critical minerals such as lithium and nickel and is, therefore a key player when it comes to manufacturing, albeit one that underperforms from a domestic value-add perspective.

The challenges around EV environmental impact are myriad: Australia’s grid is still largely fossil-fuelled for one, despite a world-leading take-up of solar, while EVs begin life with a CO2 penalty due to battery production emissions.

At the other end are issues around right-to-repair rather than wasteful restrictions on battery upgrades and finding suitable solutions to recycle or repurpose EV batteries for things like BESS at scale.

Another aspect is engaging with prevalent misinformation that states EVs are either zero-emission (false) or worse for the planet than ICE (also false). This nuance is important and the messaging must improve.

Another potential factor is batteries entering thermal runaway, aka fires, which is low in risk but high in profile. An EV fire is also an emitter of terrible toxins, on the rare occasions it occurs.

Matthew Davock

Director of Manheim Commercial Vehicles, Cox Automotive

EV manufacturing and the environment…

Commercial vehicles are at least six-to-seven years behind the car market today from an EV adoption perspective.

The LCV sector continues to learn from dynamics impacting the car sector. Overall, infrastructure and the difference in asset scalability and usage mean that the LCV asset journey differs greatly from car. From this Infrastructure, plans must be adopted and deployed creatively to succeed in the LCV sector for the future.