A typical vehicle comprises more than 25,000 parts1, each having undertaken a journey as part of a manufacturer’s supply chain. As these have become increasingly complex and globalised, driven in part by the sophistication of the electronic components of the vehicles they produce – particularly EVs – it’s fuelling a transformation in supply chain thinking. Not since the advent of Just-in-time (JIT) inventory systems and “Lean thinking” of the 1980s, has there been such a monumental re-examination.

A typical vehicle comprises more than 25,000 parts1, each having undertaken a journey as part of a manufacturer’s supply chain. As these have become increasingly

A typical vehicle comprises more than 25,000 parts1, each having undertaken a journey as part of

complex and globalised, driven in part by the sophistication of the electronic components of the vehicles they produce – particularly EVs – it’s fuelling a transformation in supply chain thinking. Not since the advent of Just-in-time (JIT) inventory systems and “Lean thinking” of the 1980s, has there been such a monumental re-examination.

a manufacturer’s supply chains. They are large and complex networks that span multiple continents and are thought to be responsible for a significant proportion of the industry’s environmental and social impact.

So, as supply chains are thought to be responsible for a significant proportion of the industry’s environmental and social impact, they are the focal point of sustainability strategies in automotive.

Supply chains are complicated, interconnected and increasingly cross-border but they are also fragile. Involving many different stakeholders, they are prone to disruption.

In this section, we ask what changes manufacturers are making in their supply chains and how are being made more resilient. We also ask how sustainability is informing those changes and what is being done to ensure the extraction of relevant raw materials is, on the whole, more ethical and transparent.

Only as strong as its weakest link

Interested parties who make up automotive supply chains include raw material suppliers, component factories, distributors, logistics companies and many more organisations besides. Split into four levels, tier 1 includes suppliers who provide parts or systems directly to manufacturers. Tier 2 and 3 supply parts that invariably end up in vehicles while tier 4 suppliers specialise in raw materials such as plastic, metals and minerals. Each level feeds into the one above it and this tangled web is exceptionally vulnerable. A delay there can mean a halt to production here. That inherent weakness is exacerbated by political and socioeconomic forces beyond any manufacturer’s control.

Events and worldwide crises have caused huge disruptions in automotive supply chains. These include the pandemic, the semiconductor chip shortage and the war in Ukraine. Other more transient happenings include the container ship that blocked the Suez Canal for six days in 2021, causing chaos in global shipping and billions in losses for the automotive sector.

More recently, the strike by UAW workers at Detroit 3 (GM, Ford and Stellantis) plants across the US has had a significant impact on production, costing the industry billions of dollars and forcing the idling of several facilities. That has had a corresponding impact on many GM suppliers, some of whom have reduced production or even shut down. As we went to press, strike negotiations were ongoing, with many commentators, including Cox Automotive’s Chief Economist Jonathan Smoke, saying GM would likely face supply chain problems if the industrial action was prolonged.

With cars now increasingly resembling computers on wheels (some vehicles contain upwards of 1,000 semiconductors), and when up to 40% of the cost of a new car is derived from its electronics2, it’s difficult to overstate both the pronounced importance and growing complexity of automotive supply chains.

As manufacturers keep net-zero goals front and centre of their business strategies, the significance of supply chains and their associated sustainability issues have grown. Supply chain resilience helps maintain production targets and therefore profits, while transparency and sustainability aspects help companies keep a focus on their environmental impact and the documentation of it.

Vertical resilience

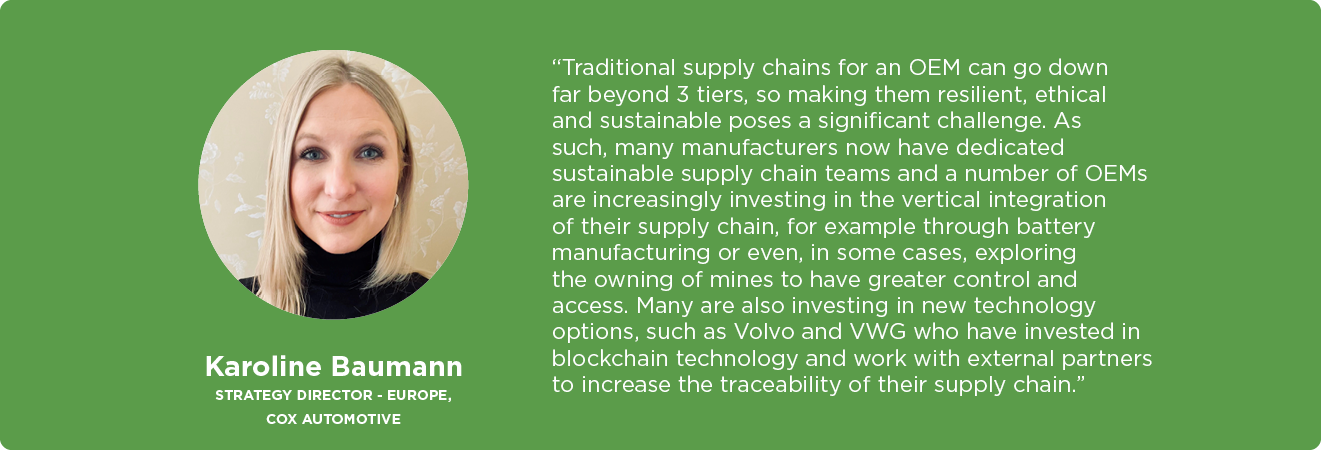

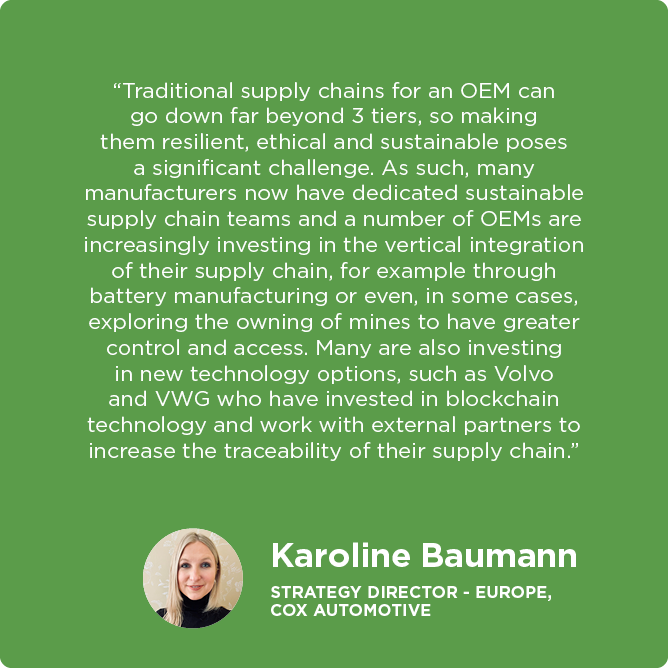

One way that manufacturers have sought to make supply chains more resilient is by making them ‘vertical’. That’s when a company owns or controls multiple stages of the production process, including the sourcing of raw materials and the distribution of new vehicles to customers. Chinese EV brand BYD has a significant degree of vertical integration, including its battery manufacturing division which is one of the largest in the world. It also has its own semiconductor manufacturing arm. Such factors mean reduced costs, increased control and inevitably better coordination of production process stages. Shortening the supply chain or, indeed, building one from the ground up, helps ensure the one quality that all manufacturers seek: certainty.

Another example of evident vertical integration in this area is Tesla. CEO Elon Musk famously summarised the supply chain risks of putting production targets in place during the company’s scaling-up phase as “production hell”. BMW too has a moderate degree of vertical integration, with its own engine, transmission and component suppliers.

Following the worldwide semiconductor chip shortage, Volkswagen Group’s Purchasing Chief, Murat Askel, revealed that the company was moving into direct purchase agreements with suppliers that it previously had a comparatively long-distance relationship with. He said that VW was also constructing a database of suppliers to help predict and react to supply chain risks ahead of time. This was similar to VW’s strategy following the 2008 financial crisis, but then it was designed to mitigate financial risks, as opposed to manufacturing ones.

Manufacturers are also improving the hardiness of value chains by working with suppliers to develop and implement risk management plans. The Global Automotive Manufacturers Association (OICA) which has several large brands as members, does work to publish data on relevant supply chains. It also researches trends in associated technology, markets and regulation changes.

Giant steps have been taken towards making supply chains more weatherproof. Some manufacturers have negotiated long-term commitments from players in different parts of the process, including shipping companies and semiconductor factories. The chip shortage that negatively impacted vehicle production in 2021 and 2022 revealed that suppliers often prioritised larger non-automotive customers who were ordering more chips. That fact has been factored into negotiations which will see manufacturers make swift recalculations.

Certainty has been the driver in these discussions, but where does sustainability fit in?

ESG and collaboration

Clearly, collective goodwill fuelled by an overarching desire to lower CO2 emissions to aid the climate change fight is not enough.

That’s why governments and campaigners throughout the world are introducing stringent laws or calling for immediate action.

Driven by legislation, businesses are eager to flex their green credentials. The emergence of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG), a framework for assessing a company’s sustainability and that of its partners, is a prime example. In automotive, ESG allows a manufacturer to assess and manage the risks and impacts of its suppliers through an environmental, social and policy lens that’s separate from any financial considerations. For example, a company will want to steer clear of suppliers with a poor environmental record or those that engage in questionable employment practices. As a result of ESG, businesses can disclose climate-related financial risks and opportunities as part of the voluntary framework: The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The TCFD has global support from a wide range of organisations and businesses.

Demonstrations of ESG in practice also include Volkswagen’s announcement in 2019 that it would introduce a worldwide sustainability rating for suppliers, with a focus on human rights, environmental protection and corruption. Ford announced last year that its Bronco Sport model would include parts made of 100% recycled ocean plastic, collected by workers in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. It is being used to make wiring harness clips in the vehicle. General Motors has outlined plans to use 100% renewable energy for its US manufacturing by 2030. It is also working with suppliers to develop low-carbon processing methods.

Audi has been a member of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) since 2009. It’s an international independent standards organisation that helps companies take responsibility for their environmental impact. The German manufacturer uses GRI standards to report on its sustainability performance, including that of its supply chains. Meanwhile, Stellantis announced a joint venture with metal recycling specialist Galloo this year3. Together, they intend to implement a service to recycle end-of-life vehicles. This measure, and others mentioned above, show how seriously manufacturers are taking the “circular economy” concept.

A simpler way to understand ESG is that it concerns product, people and policy; how goods are made, who by and in what conditions, as well as the regulations that underpin manufacturing processes. As climate change fears have grown, ESG has been bolstered by the fact that many investors are choosing to factor sustainability issues into their business choices. Financial institutions throughout the world are increasingly relying on ESG rating agencies to assess a company’s ecological and socioeconomic performance.

In 2017, a partnership of 16 manufacturers including BMW, Ford, Ferrari and Toyota, formed to improve sustainability throughout their respective supply chains.

Drive Sustainability has a number of goals such as increasing the social, ethical and environmental performance of suppliers and manufacturers. It’s focused on risks to its collective interest but also demonstrates a willingness to improve the working conditions in those chains.

The partnership’s most recent Sustainability Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) (first launched in 2014) reports that the automotive supply chain continues to “…develop robust sustainability foundations. However, predominant low scores on human rights shows there is more work needed to address increasing legislative expectations in this area”4.

Collaborations such as the above demonstrate a collective will to apply sustainability principles to automotive in areas that are a significant source of the industry’s environmental impact. Government mandates are pulling in the same direction.

Legislating circularity

Governments throughout the world are intervening to force all kinds of industries to be cleaner, greener and more sustainable. We’ve already mentioned how, in the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is seeking to reduce emissions by, among other things, incentivising businesses to invest more in EV manufacture. Meanwhile, in Europe, Rules of Origin (RoO) will inevitably have an impact on the sustainability and circularity of supply chains as the rules encourage the use of local materials and components, i.e., parts that have travelled fewer miles to reach the factory floor.

Another relevant trade policy that places a tax on imports of goods and services that have a high carbon footprint is the EU’s Carbon Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Designed to address “carbon leakage”, where businesses relocate to counties with less stringent climate policies to avoid carbon costs, it was expected to be implemented this year.

Also, this year, Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act was introduced. It means that companies with at least 3,000 employees (and which are based in Germany) must make reasonable efforts to ensure that there are no violations of human rights and environmental obligations specified in the law in their business operations and the relevant supply chain. This applies regardless of whether the relevant activity is carried out domestically or in a foreign country. Transgression of the act and/or reporting obligations may lead to fines of around €8 million, depending on the severity of the violation. Companies with a turnover of more than €400million may be fined up to 2% of turnover for breaches.

The European Union’s “directive on corporate sustainability due diligence” echoes the German act and its core elements are “bringing to an end, preventing, mitigating and accounting for negative human rights and environmental impacts in the company’s operations, their subsidiaries and their value chains”. EU member states must enforce the measure which comes into force next year.

In the US, since 2010, California has had its Transparency in Supply Chains Act. This law obliges companies that sell products in California to disclose information about their efforts to eradicate slavery and human trafficking from their supply chains.

At the federal level, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) changes US policy on China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to ensure American automotive companies are not funding forced labour among ethnic minorities there. The act came into force in 2022 and means any company that imports goods from the Xinjiang region needs to certify that those goods were not produced using forced labour. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 is the most significant piece of recent US legislation about supporting supply chains; however, it includes measures for the development of new battery technologies, as well as their recycling.

Making EV manufacturer more sustainable

While EV adoption is the focus of decarbonisation throughout the developed world, significant questions must be asked about how their manufacture can be made more sustainable.

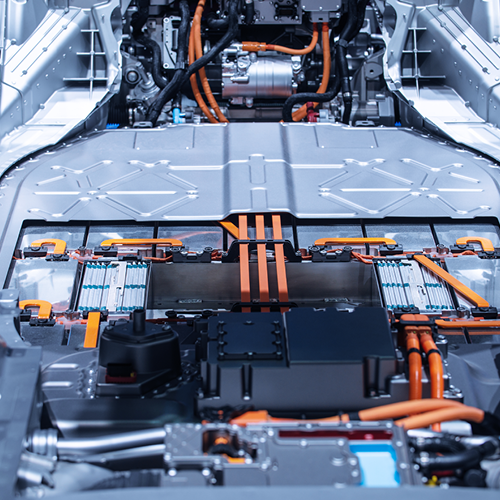

The environmental implications of how they are made are complex and concerns include how raw materials used in EV batteries, such as lithium, cobalt and nickel are mined and processed. They come from countries including Chile, Australia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

There are also energy-intensive processes involved in manufacturing the batteries, which, according to reports, produce a significant amount of CO2.

Sustainable manufacturing is invariably aimed focused on reducing environmental harm and conserving natural resources. New methods to harvest lithium, such as “direct lithium extraction” are evolving to help make mining less water-intensive. Sustainable battery production is showing encouraging signs of evolution also. Practices such as deploying more renewable energy resources in battery production, reducing waste and sourcing materials with a greater emphasis on circularity, are helping.

The role of technology

One of the challenges faced by automotive, amid the increasing legislation and ESG strategy, is that it’s harder to ensure supply chains are sustainable overseas compared to those on home soil.

Technology is playing a vital role in this area when it comes to the mining of materials crucial to EV battery manufacture, including cobalt, nickel, lithium and manganese.

The sectors producing these minerals are plagued by challenges, ranging from health and safety to human rights. These problems occur in industrial, artisanal and small-scale mining, where cobalt and copper are commonly extracted. In countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) there have been widespread reports of harsh working conditions and even child labour.

Blockchain technology has become a key means of tracking activity and will be a crucial element of battery passports. It’s an advanced database mechanism that allows transparent information sharing with a business. At the recent SMMT Electrified event in London, Yue Jin Tay, Vice President of Product and APAC of Circulor, spoke on the subject.

His company specialises in responsible sourcing and recycling. He said that blockchain helps keep track of every item of material used in a battery’s manufacture.

“What goes in the cathode, the anode, which mine it comes from, the chemical components that have gone into it, all these elements can be tracked throughout a battery’s lifecycle”, he added.

Such innovations can help manufacturers make clearer strategic decisions where supply chains are concerned to move in a more ethical direction.

Consumers have never been more aware of the environmental and social impact of the products they buy, whether it's smartphones, food or cars. Climate change fears are driving consumer choice and wise manufacturers have reacted to understand, record and improve the sustainability, morality and circularity of their supply chains. Government regulation is putting increasing pressure on manufacturers too, while investors who see sustainability as a necessary attribute, are also playing their part in altering the course of brands throughout the world. All these factors are shining a stronger light on manufacturing, making sustainability in automotive more sustainable.

PERSPECTIVES

References

- What is the automotive supply chain?

autovista24.autovistagroup.com/news/what-is-the-automotive-supply-chain/ - Electronics make up 40% of a new car’s cost

www.autoexpress.co.uk/news/352300/electronics-make-40-new-cars-cost - Stellantis forms joint venture to recycle end-of-life vehicles and create a more circular economy

electrek.co/2023/06/05/stellantis-joint-venture-recycle-end-of-life-vehicles-galloo/ - Drive Sustainability Launches First Intelligence Report: Elevating Due Diligence and Enhancing Sustainability in the Automotive Supply Chain through the Sustainability Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ)

www.drivesustainability.org/mediaroom/drive-sustainability-set-to-launch-first-intelligence-report-elevating-due-diligence-and-enhancing-sustainability-in-the-automotive-supply-chain-through-the-sustainability-assessment-questionnaire-s/

Jonathan Smoke

chief economist, cox automotive INC.

Making supply chains more resilient, sustainable and ethical…

OEMs and suppliers are investing to bring more of their supply chain into the US, particularly for EVs. Following the IRA, there has been $65 Billion+ invested in building out a supply chain in the US across mineral mining & processing, component and battery production, and recycling.

Mathew McAuley

Director of Strategy & Marketing, Cox Automotive Australia

Making supply chains more resilient, sustainable and ethical…

Increased levels of vertical integration are top-of-mind, whereby OEMs take critical software and hardware development in-house to own the intellectual property (IP) and hedge against suppliers' production issues.

Australia’s network of automotive suppliers has had to either pivot or die since the end of local major-scale manufacturing here. However, some have found ongoing work with smaller operations such as Walkinshaw, which re-engineers big American pickups to right-hand drive for sales in official OEM dealers.

The ethical and sustainability aspects often come down to mineral procurement, which naturally is a major focus for a net mineral exporter like Australia. Technologies such as blockchain can be helpful to track one’s supply network as well.