Will e-fuels save the combustion engine?

In this section, ICDP explore whether e-fuels have a future in the 'Net Zero' world.

Continue reading

Steve Young

Managing Director of ICDP

In early March, progress towards formal agreement on the post-2035 emissions regulations, which form part of the Net Zero emissions policy, was interrupted by an intervention from the German Transport Minister, who suggested that the door should be left open for ICE after 2035 if they are running on synthetic e-fuels, so still broadly meeting the zero emissions objective. These manufactured fuels require energy-intensive processes and are still significantly more expensive than fossil fuels. Moreover, they are not the same as biofuels promoted by Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, and some other states as part of the same last-minute intervention.

It seems likely that he was responding to strong lobbying from the German car industry but raised significant questions about whether this approach was even viable and if it might provide an opportunity to sustain ICE cars in the parc over an extended time if the fuel could be made affordable. Unsurprisingly, the environmentalists, including his own coalition partners in the German Green Party, were strongly against the move. Still, it was a crack in the wall in terms of the path to the combustion engine's demise.

The development of e-fuels is developing quickly, with a particular focus on using them blended with fossil fuels to ease the production and cost transition. Blending just 5% e-fuels with conventional fuel will save 60 million tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. Hence, it makes a meaningful difference, and progressing the blend to 100% over time is a way to allow production capacity to be brought onstream progressively as costs come down. Whilst e-fuels are not available or affordable for general use today, there is a potential that it could be a viable longer-term option – even by 2035, when we have been led to expect that the combustion engine will disappear from sale in Europe.

"Blending just 5% e-fuels with conventional fuel will save 60 million tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. Hence, it makes a meaningful difference, and progressing the blend to 100% over time is a way to allow production capacity to be brought onstream progressively as costs come down."

Steve Young, Managing Director of ICDP

At the end of the month, a concession was agreed by the European Commission that would open the door to e-fuels. However, the concession details have not yet been established and will be contained in regulations which will be published in some months. The key points agreed, however, are that a new vehicle category will be created for combustion engine cars that can only run on carbon-neutral fuels. It's assumed that this will be done through some form of monitoring in the car to ensure that a carbon-neutral fuel is being used, which implies perhaps a chemical marker being included in the fuel with a related sensor somewhere in the fuel system.

The existing 2035 legislation will be locked into EU law first, following which a new regulation will be proposed to create the new vehicle category and define how the e-fuels concession will be applied. The Commission has committed to bringing this regulation forward in a form which is difficult under EU procedures for other countries to block, giving Germany some confidence that the regulation will be enacted even whilst protests continue from other states and lobbying organisations. Furthermore, the concession only applies to e-fuels and not to biofuels supported by Italy and some other states but are not carbon neutral over their lifecycle.

The concession triggered an immediate response, with the French Transport Minister insisting that the choice for 2035 must be to get out of combustion engine vehicles. However, this signal should not be blurred by allowing them to continue even if operating on carbon-neutral fuels. Transport and Environment, a leading lobbying group extremely active in the Dieselgate saga, produced their analysis and organised a high-profile protest by the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. They claimed that e-fuel cars would replace between 26 and 46 million BEVs by 2050, which equates to around two million units a year which could be over 10% of the European market. They also said it would derail the decarbonisation of the new fleet and allow conventional oil to be used in the existing fleet post-2035.

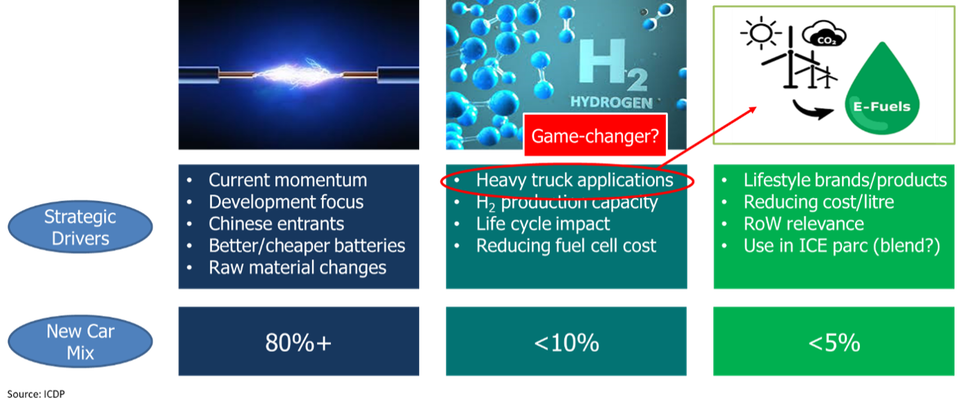

The ICDP view is that this concession will not fundamentally change the future powertrain mix for Europe from 2035, with BEVs remaining the core technology and potentially hydrogen FCEVs in a supporting role.

When considering the various forces at play, BEVs now have strong momentum. They are the focus of development for most manufacturers and have been adopted by Chinese manufacturers under government pressure to allow them to leapfrog the established players. We will also see better, cheaper batteries using solid-state technology and different chemistry. This will change the raw material demands addressing some of the current concerns about the reliability of supply and ethical sourcing.

Hydrogen is currently the favoured solution for heavy truck applications but will require heavy investment in production capacity and fuelling infrastructure. However, it is potentially a better solution than BEVs when considered end to end from raw materials through to end of life. Again, as volumes increase and experience is gained, we will likely see a reduction in the cost of fuel cells.

E-fuels, in our view, are likely to be restricted to lifestyle brands and niche applications where infrastructure constraints may restrict the relevance of BEVs or FCEVs. However, the production cost per litre will undoubtedly reduce over time with growing volume. Therefore, there is real potential for it to be a more relevant option in the rest of the world than in Europe, China or possibly North America. It also provides a genuine environmental benefit if the availability of e-fuels at a reasonable cost would allow the older parc to switch from pure fossil fuels to e-fuel or an e-fuel/gasoline blend.

Considering all of that, we still see BEVs as representing the vast majority of the new car mix in 2035, with hydrogen potentially having up to 10% share but e-fuels probably little more than 5% share. What might be a game changer would be if the availability of e-fuels at the right price allowed these to be adopted in the heavy truck sector without the need to invest in hydrogen fuelling infrastructure but also dramatically increasing the volumes and therefore helping to drive costs down.